It was Buzz Aldrin -- and not Neil Armstrong -- that was the unsung hero of the first lunar landing.

Neil Armstrong will forever be Neil Armstrong. The man with that one small, first lunar step, that was also that one giant step for mankind. However, to us computer nerds, The Man on the moon, back on that July day 50 years ago, was Armstrong's co-pilot Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin.

Because while Armstrong may have been the first human on the moon, Aldrin was its first software hacker.

Like most humans, we stood humbled this week by the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing. Some of us are lucky enough to remember the 22 hours Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin spent on the lunar surface: Aldrin kicked sand and took communion. Armstrong spoke to all of earth and became celebrated field geologist. Indeed, his collection of lunar rocks dazzles to this day.

But what’s indispensable about the Apollo 11 flight to the moon, for those who explore the cold frontier of intelligent machines, is how the lunar landing was a watershed in the development of computers and software. It’s often forgotten that the lunar module was not just a two-man pop-up camper optimised for space travel. The lander was one of humankind’s earliest fly-by-wire vehicles. It was not controlled by linkages that physically connected to wing flaps and rudders. Instead all levers, buttons and switches on the lander were routed into a central, entirely electrical control hub that sent coded instructructions to rockets, thrusters and control systems. The lunar module’s all-electronic control not only saved weight and power, it made flying a sharable gig between pilots and machines. In fact, the vast majority of the lander’s flight was handled by computer. A computer that was programed some of the first reasonably well-engineered software ever written.

“I look at Apollo 11 as the first time that software landed on the moon. It really was the dawn of the digital age,” said Margaret H. Hamilton, the Colossus Programming Leader for the Apollo’s guidance and navigation system, who is given co-credit as one of the inventors of modern software engineering.

How man and computer got along, during the 240,250-mile voyage to the moon, has much to teach us about solving complex computational problems. “In the end, (the Apollo 11 landing) becomes a critical partnership between human and machine where each party made up for the other’s shortcomings,” explained Kevin Fong, a UK-based medical anaesthetist, who worked extensively with NASA and recently hosted the BBC’s must-listen 13-episode podcast on the Apollo 11 landing called 13 Minutes to the Moon.

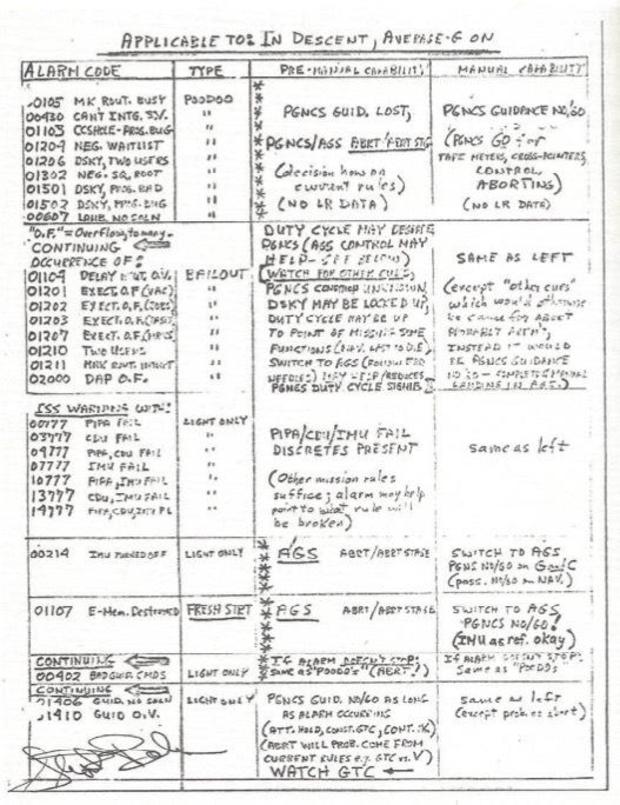

Fong's podcast digs deeply into the relationship between hardware and man, by weaving together live Apollo mission control lunar transmissions, with scrupulously researched present-day interviews with NASA controllers, technicians and astronauts. The series does a startling job of revealing the full range of shortcomings that man and machine had to fight through to get to the moon. The onboard computers, which featured just four kilobytes of flexibly programmable read/write memory, got overloaded early on. On Apollo 11’s final descent, ground radar systems and radio antennas were mis-deployed as to an overload the fragile computers. Similar to today’s denial-of-service attacks on a website, too many instructions flooded the computer and “non-essential systems,” including the lunar module’s computer control panel, went down. Ground controllers diagnosed the trouble by relying on a handwritten list of error codes that rested taped to a desk a 24-year-old backroom controller named Jack Garman.

Armed with nothing but this hand-written cheat sheet, Garman diagnosed that the “1201” and “1202” errors being called in from this control panel on the lunar module were manabable computer slowdowns. And not mission critical bugs that would scrub the mission “If it were up to me, I would have probably called an abort at that time,” said Don Eyles, one of the programmers of the original lunar module software.

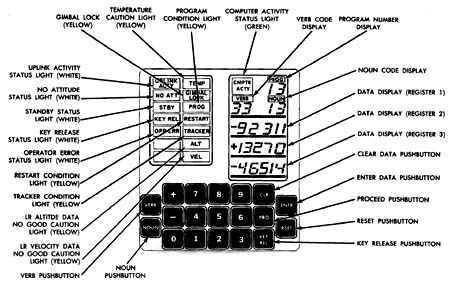

Even when the lunar module’s computer was working as intended, using it was not like typing into the iPhone. The lunar lander was controlled by a primitive numeric control pad that required commands like “P64” to begin a powered descent or "P63” to initiate a final approach.

These commands prompted software that remains must-see for modern programmers, used to sloppy open-source and commercial code. Branded as Colossus by its MIT programmers, the lander's software package is considered a work of computer programing art by science historians. The code was developed under strict software engineering standards that were invented to write the program. Every line was tested thousands of times and hand refactored to be as efficient as possible. The working scripts for Apollo 11 can be downloaded and modified from this repo on GitHub. You won’t be the only nerd who can't help messing with the scripts. Even 50 years later, there are nearly 300 comments, more than 70 contributors and an active branch of the program.

Somebody somewhere is still perfecting the code as if the Lunar Lander may still be going back to Tranquility Base.

Aldrin: The Machine’s First Master.

Out of this caldron lunar man/machine chaos, an unlikely hero emerges. A hero who gets oddly little mention in the 50th Anniversary hype we feeling today: Armstrong's partner in the lunar descent, Buzz Aldrin.

Ostensibly, Aldrin was the pilot of the lunar module. But Armstrong manned the controls and flew the craft during the final moments of the descent. Armstrong famously nearly ran out of fuel as he search for a place to land. But Aldrin did not sit by quietly. He was fully busy managing the on-board computer and systems. Aldrin was smack in the middle of the densest, most dynamic thinking-machine problem probably that world had seen to date.

But Aldrin was not interviewed for 13 Minutes to the Moon podcast. And there is little coherent public information from Aldrin’s books and comments on his exact role during the final descent. Most of his life was spent battling depression, booze and multiple marriages. It feels like Aldrin almost kept it to himself how the critical final minutes getting to moon unfolded. Maybe he knew the price of scuffing the scripted “small step/giant step” narrative of Armstrong and Mission Control. Or maybe, for Aldrin, it was just another day on the frontier of thinking machines and foolish humans.

But if the recorded events of those final minutes before the Eagle landed were even a quarter true, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin was a stone cold computer problem-solving assassin. This man was the unsung hero of the Apollo 11 landing. In many ways, he pioneered many of the principles we try to live by around here as we pioneer the telling of truth from fiction in videos and sounds.

Here’s what Buzz Aldrin reminded us to keep in mind as we solve the machine learning problems we are managing.

Buzz’s 5 Lessons In Managing Complex Computers

1: Enjoy the Ride: What jumps out about the lunar landing is how much Aldrin luxuriated in the process. On the final orbit, before the final descent, the spacecraft emerged from radio blackout from behind the moon, Aldrin was anything but tense. He had the grace and good humor to point out how lovely the solar system. Over the open communication line one can hear his famous line “That’s the Earth right out the window,” which draws a startled silence from Houston's flight directors. You can just imagine a collective "That’s Buzz daydreaming again" over at Mission Control.

Learning to lighten up and enjoy the wonders of what we get to see is a critical lesson we forget all the time.

2: Speak Truth to Power, Gently: What also emerges from studying Apollo 11 landing is how Aldrin was a master of providing information-starved central networks with just the right amount of data and narrative that informed, while still keeping large teams focused on the practical problem at hand. Communicating was not trivial for an Apollo program that faced several waves of human tragedy. The most notable was the awful Apollo 1 fire where stronauts Ed White, Gus Grissom and Roger Chaffee were baked alive, essentially because NASA and its contractors could not stay focused on the common problem of building a fireproof space capsule.

The second, and much less famous casualty, was Apollo 7. This was the first manned mission after Apollo 1, when all automated systems were carefully tested on a live mission to space. Apollo 7 was placed under the command of the otherwise reliable Wally Schirra. But this son of a U.S. Navy admiral was steeped in the military tradition of decentralized command. Schirra started to question Mission Control’s choices during the flight. Bickering soon broke out between the crew and controllers. Eventually Schirra refused to follow orders for wearing a helmet during re-entry. The actual logs from that mission have been suppressed, but Schirra’s actions got him and his crew blackballed from the NASA program.

Aldrin learned to pick his words carefully. During the final descent, it was Adrin that fought through the major system errors that threatened to overwhelm the mission. And it was Aldrin who joked, “Better than the simulation,” during a critical moment in the landing. Many Apollo team members remember that was the critical turning point that gave the nervous landing team the confidence to press on for the moon.

NASA could trust Aldrin to be the out-of-the-box thinker who still managed to act effectively inside a very boxed-in culture. We struggle with the balance of innovating vs. immolating others every day.

3: Guess Credibly: What truly makes Aldrin fascinating was how he was able to feed critical flight data to Armstrong and Mission Control, even though such information was not easily available. Throughout the landing, Aldrin managed the half-dozen or so system errors that were both slowing critical processes on board and shutting down his command display. Yet throughout the 13-minute descent to the moon’s surface, Aldrin calls out critical data to Armstrong and controllers, even though it was not entirely clear where the data came from.

Over and over, Aldrin was able to reason out the important data inputs: He noticed that the computing slowdown came during the computationally burdensome task of comparing the real rate of descent with the computer calculated the rate of descent. The variable was called Delta-H, and in the transmission tapes you can hear Aldrin off-handedly suggesting to Houston that Delta-H was a problem.

The exact details of how that was reasoned out and Aldrin’s exact keystrokes can be found in Tales from The Lunar Module Guidance Computer, Don Eyles paper on the core systems errors during the landing. There are also excellent explanations of what Aldrin did on forums like Stack Exchange. But the importance of how Aldrin sussed out the problems with the onboard software was not lost on space historians.

“To me, that is the moment when the complex subtle human machine network solves the problem and moves on,” says David Mindel, author of Digital Apollo, in a podcast.

4: The Feel for Data Narrative Aldrin played his role, guidedhis team, communicated calmly and enjoying his day in the problem-solving ethers. But that is are not what make him unique. Other astronauts played similar roles on their lunar landings. What makes Aldrin indispensable how he filled in the narrative gaps that the on-board computer could not manage. As the lander closed in on the moon's surface, it became clear that large boulders would make the chosen landing site unsuitable. To find another landing location, Armstrong and Aldrin had to locate a landing spot by eye. The team relied on something called the Landing Point Designator, or LPD. Basically, the LPD is an Z and Y axis that marked in degrees on the lander window. The numbers took angular readouts from the on-board computer and matched them to a physical landing location on the ground.

In the image below, trythe LPD yourself. Say the computer readout read“40,” that would mean you would land on the bit of ground right next to the "40" on the grid to the right of the image.

The LPD looks simple. But it was not. Historic Space Systems has a neat online simulator if you want to see for yourself, why it took 2,000 training sessions to learn to land a lunar module. Be warned: Trainees endured 1,000 simulated crashes in the process.

During the final landing sequence, Armstrong relied on Aldrin to synthesize this information to give him clear LPD readouts, so he could eyeball the landing location. “LPD. LPD,” asks Armstrong over and over during the final moment. And Aldrin calmly walks the answer back: “45, no, 47.” It all sounds calm and organized. But think about what's happening here: At this point in the descent, the lunar module was into its sixth serious system alarm. The onboard computer shedding non-essential tasks, including the readouts for various data points like the LPD.

We have no idea exactly what happened. The details are not documented. But if you listen to the communications from those tense moments, where is Aldrin getting that LPD information from? To us, Aldrin is just kind of giving out his estimates of the LPD, altitude and rate of descent. There was plenty of other information to help Aldrin locate spacecraft in relation to the ground. There were stars. There were other points he could use to triangulate his position. Aldrin had pioneered walking in space, setting a record for extravehicular work of 5 1/2 hours! He had built a reputation for being so immersed in the mathematics of orbital mechanics that he’d been nicknamed “Dr. Rendezvous.” And so, on that day 50 years ago, with Armstrong flying by hand, burning nearly all the fuel in the lunar module, there was Aldrin calmly reading off the data that may or may not have been actually in front of him:

- “3 feet. 2-and-a-half down.”

- “3 feet. 4-and-a-half down.”

- “Drifting to the right a little.”

It’s problem solving genius in action, considering the situation. And even though Armstrong uttered the famous quotes everyone remembers for stepping on the moon, it was Aldrin who actually made the furst call of a human-made object touching the moon. He was the one who called out “contact light,” which was the indicator on the control panel that fired when the three-foot extension, that stuck out from the bottom of the lander, had touched the lunar soil.

It was probably the only real firm piece of data Aldrin had throughout the landing. That it was stopping the engines and stepping on the Moon. Whew!

Give Us 10 Aldrins, Please

Of course, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin was not only famous for getting to the moon. He has suffered from deep and terrible alcoholism. He has a reputation for being temperamental and probably chucked his NASA career for his flaws. You can read all about it in Magnificent Desolation, Aldrin’s book about adjusting to life back on Earth.

When Aldrin touched down, he famously took time to take communion. He was the first and only Apollo astronaut to do it. And when you realize what the man was capable of, it all makes perfect sense. Buzz Aldrin, give us even a few of you and we could conquer not just the moon, but any world.

We hope you realize what you have achieved.