AI Language Models are helpful. But are they thoughtful? Not even close.

Robert Frost won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry four times essentially for crafting sentences like this: ”Thinking isn’t agreeing or disagreeing. That’s voting.” Too bad San Francisco-based artificial intelligence shop, OpenAI didn’t think to read more Frost before developing its commercial chatbot, GPT-3.5.

Case in point: GPT-3.5’s answer to the simple-seeming question of “What is Artificial Intelligence?”

On its first try, GPT-3.5 crafted together a reasonably coherent essay on AI as computer systems that perform tasks that “would typically require human intelligence.” GPT-3.5 then generated a narrative that AI is a broad field, made up of tools that can learn over time and be broken down into two main categories: narrow artificial intelligence that solves problems one at a time, and more general artificial intelligence that can solve any problem. All seemingly intelligent enough.

Until, that is, the tool was asked the same exact question a few more times. Then GPT-3.5 felt like ventriloquist Jeff Durham and his dummy Achmed the Terrorist on a bad night. It’s not clear who, exactly, is speaking.

In repeated prompts for definitions of AI, GPT-3.5 offered up the exact same introductory concept of computers performing human tasks. Then it crafted various lists of applications and the generic differentiation between narrow and general artificial intelligence. Even stranger, GPT-3.5’s styptic AI narrative was echoed by other machine-language tools, like GPT-4, Claude, and Bard. These are the next-generation language models created by OpenAI and other firms, like San Francisco startup Anthropic and Google.

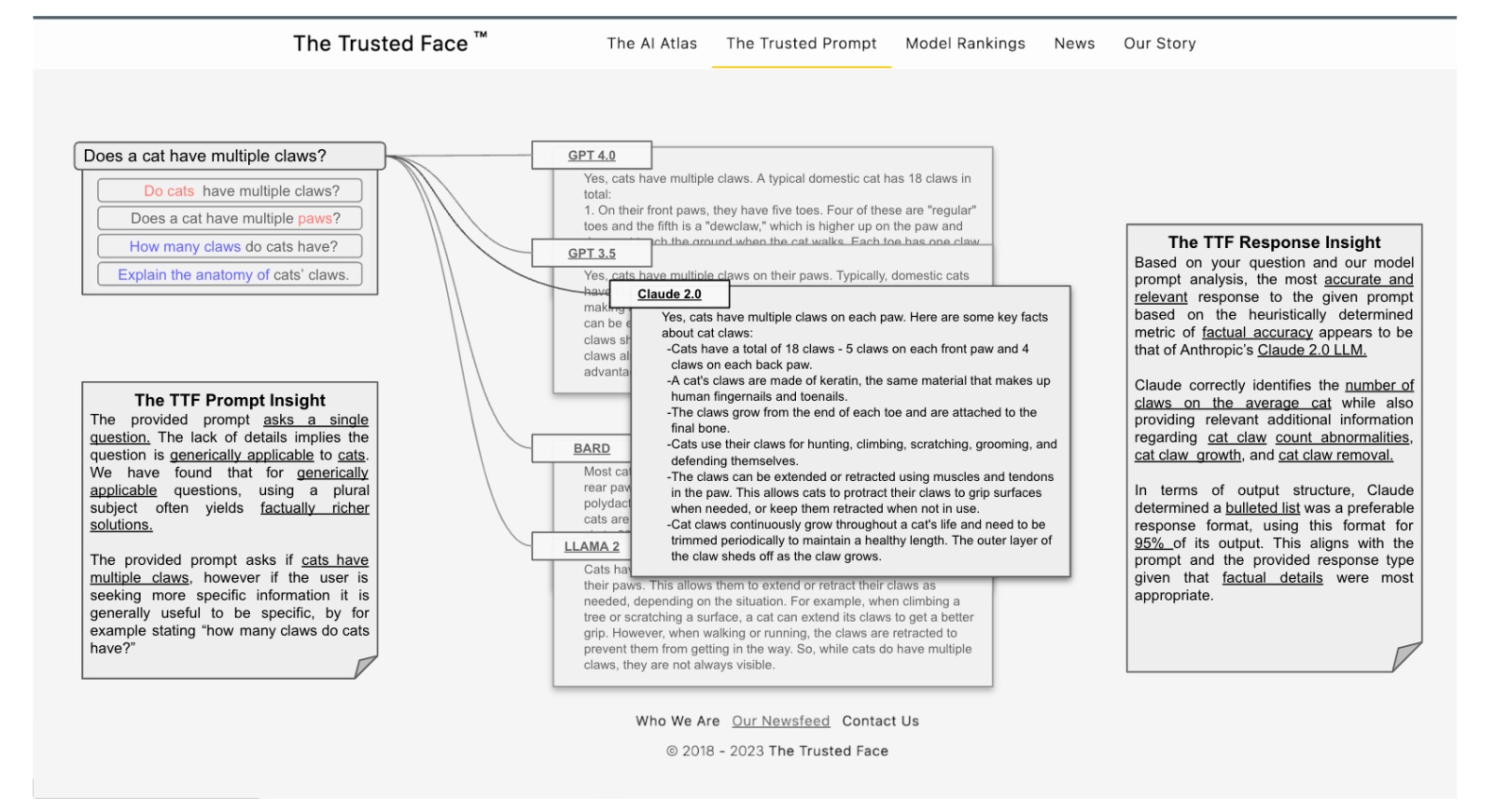

Throughout roughly a dozen hand-entered queries into various language models, all responses stuck with the tightly grouped machine-think about AI as based on human-like capabilities, lists of intelligent functions, and the core idea of narrow vs. general artificial intelligence. In fact, the results are so similar that we were prompted to develop an automated tool to query language models at true web scale to more thoroughly test what’s actually happening. We’ll share verifiable data when we get them.

But even the most basic by-hand fact-checking of the answers we got from various large-language models indicate that relative performance, technological pedigree, and training resources had little effect on various models' levels of thought, at least as Frost defines it.

That lack of thinking is inexplicable considering the breadth of perfectly thoughtful resources readily available to all these models.

Thinking Beyond Machines

Benchmarks for thoughtful analysis of AI are emerging from unlikely places: about the most intriguing is the once close-to-obsolete Encyclopedia Britannica, which started publishing definitions of various topics all the way back in 1768. And its 2023 essay on Artificial Intelligence diagrams exactly what a well-thought explanation of AI should feel like. Encyclopedia Britannica makes AI’s shortcomings clear.

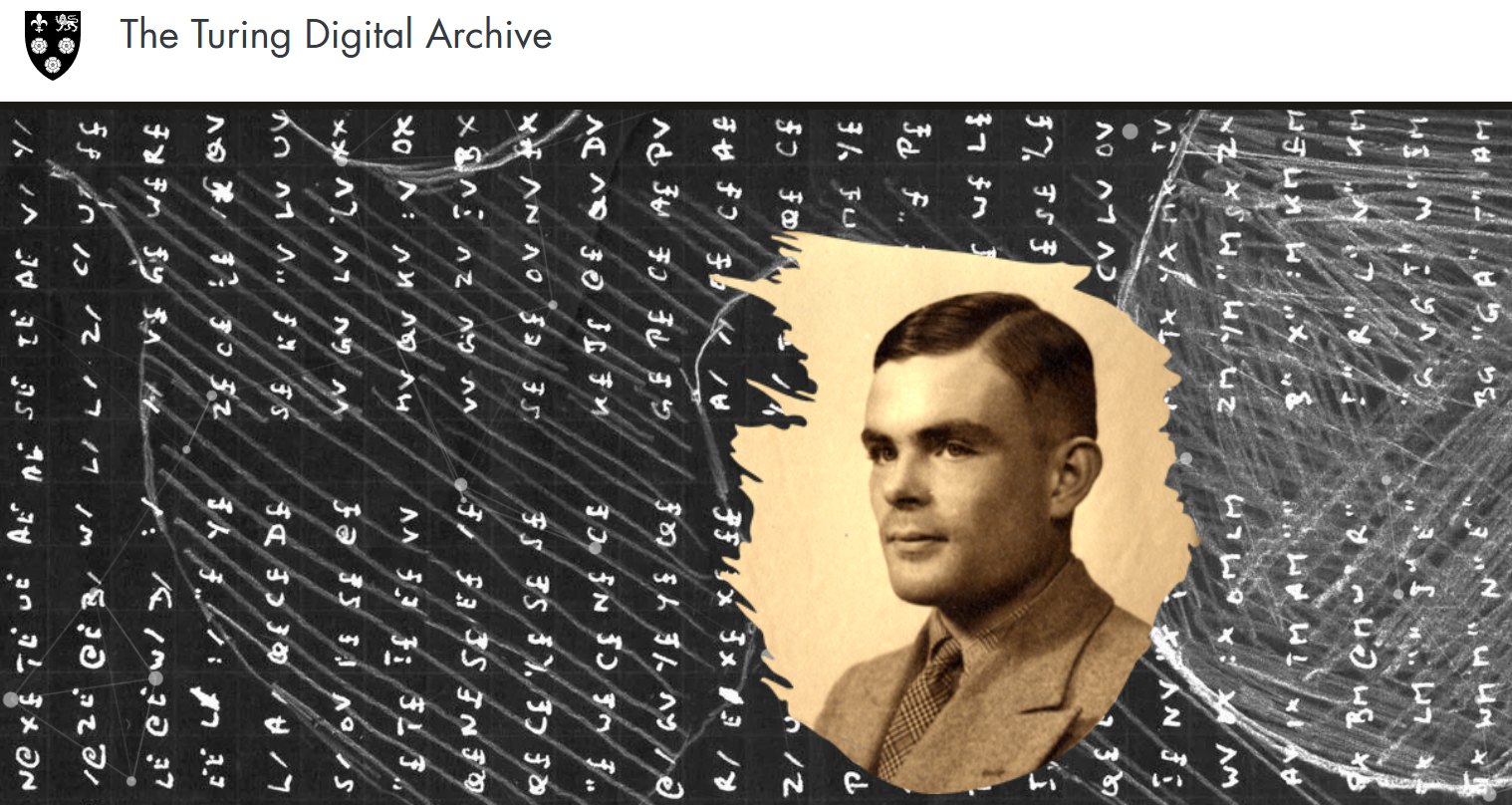

For starters, Encyclopedia Britannica found a truly unique human expert, named B. Jack Copeland, to tell the complex story of Artificial Intelligence. Copeland is not a software engineer, nor does he design robotics or have access to vast investor wealth. Instead, Copeland is a professor of the arts at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand, with multiple degrees and awards in cognitive science and the respective philosophies of logic, computation, language, the human mind, and religion. In his spare time, Copeland is also the director at the Turing Digital Archive for the History of Computing at King’s College in Cambridge, where he archives and studies the benchmark works of the human who played a key role in developing machine learning, Alan Turing.

Copeland has the philosopher’s flair for putting AI into a truly thoughtful context. For him, the narrative is all about “the ability of a digital computer or computer-controlled robot to perform tasks commonly associated with intelligent beings.”

Note how careful Copeland is to extend the reach of machine intelligence into robotics, which is by far the largest commercial application. And he does not limit intelligence strictly to humans. Instead, Copeland’s far more precise take is on the “intellectual processes characteristic of humans” that have shown, since the 1940s, the ability to carry out “very complex tasks.”

And Copeland is quick to think out loud about AI’s limitations: “There are as yet no programs that can match full human flexibility over wider domains or in tasks requiring much everyday knowledge.”

Copeland knows what really matters when it comes to AI is not how intelligent machines work, but how intelligence itself works. Here he makes the critical, thoughtful point that the simplest human behaviors are “ascribed to intelligence.” Meanwhile, even the most complicated behavior from something like an insect is not. The reason? Insects struggle to adapt to change, while humanity’s combination of learning, reasoning, problem-solving, perception, and language make us change-ready for a dynamic world.

Copeland’s analysis of each of those functions reveals how intelligence is about the relationship between those various skills. His breakdowns on learning -- for example, of trial and error, rote memorization, then the more complex generalization -- are the best we are aware of. His biographical take on Turing’s development of basic AI concepts, like limitless memory and a “scanner” that moves back and forth through that memory, humanizes the seemingly opaque processes behind machine learning. Copeland ends with reasonable steps on managing and developing AI and questions about its future.

Copeland deserves real credit for widening the artificial intelligence discussion so both human perception and computer performance matter. He isn’t agreeing or disagreeing about AI. He’s thinking about it. What's critical to understand is that thinking is readily available to state-of-the-art large-language models. Copeland's essay sits in the wide open Internet, as a trusted credible source by all major search engines. His essay must have been been analyzed by major commercial language models, like Bard, GPT3.5 and others.

Yet, not a whiff of Copeland's analysis has found its way into any of those popular models.

That raises the simple, yet profound, question: why?